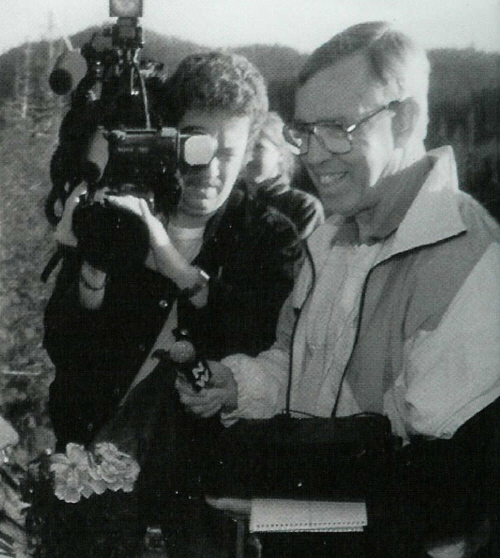

The George Garrett Story

1996 - Jack Webster/Bruce

Lifetime Achievement Award

2004 – BC Association of Broadcasters

Lifetime Achievement Award

From edited news dispatches

(1) Journalist George Garrett was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Radio/TV News Directors

Association at a ceremony in

Garrett spent 43 three years at CKNW, retiring in

1999.

His contacts in this province are legendary. It was

Rafe Mair who first called

Garrett the ‘Intrepid Reporter’. But it was his work covering the B.C. Pen

riots and as an undercover tow truck operator to expose a scam in 1978 that

gained the

A couple of days before Garrett retired, former NW

news director Warren Barker said thousands of people had been entertained,

informed, helped and sometimes educated by his news coverage. "I cannot

begin to count the number of times George's splendid performance made me, as

his boss, look good," he said.

Current news director Gord

McDonald said: "Maybe what is most important about George is his

compassion. His stories at times may have caused controversy and helped ruin

careers, but George didn't hurt people, whether it was contacts or reporters

who were competitors, he was never mean.

"While George's ability to break stories was unparalleled,

even greater was his integrity. Contacts trusted George completely. In a

competitive business that can often get nasty, George earned the respect and

friendship of other reporters. "Within this business, George was a

competitor without enemies, and that is a rare thing indeed."

(

(2) It was a veritable who's who of the old boys’

network as reporter George Garrett was roasted and toasted upon his retirement

after 43 years at CKNW.

And what a list of guests! Among them: Supreme

Court Justice Wally Oppal, former PM Kim

Campbell, Liberal leader Gordon

Campbell, former Vancouver police chief Bob Stewart and a host of 'NW types,

including Bill Good, Philip Till and the irascible Rafe

Mair.

But the man of the hour was Garrett, who throughout

his career was generally regarded as a good friend of the police, as evidenced

by the sheer numbers of

Its likely Chambers passed on the event after

Garrett broke the story of his encounter with a police counter-attack

roadblock, where it was learned that the chief had consumed a few glasses of

grog that particular evening. By the way, nice touch on the part of CKNW to

carry the roast live. It was a most fitting end to George Garrett's

distinguished radio career. (Province Joe L:eary 1999)

(3) Journalism in

I first met

George when I was a student reporter for The Sun in the late 1970s. I remember

his willingness to explain the craft to fellow journalists, with advice to

rookies and tips to veterans. Subsequently, while working for the B.C.

Federation of Labour and Premier Glen Clark, I was on

the receiving end of the microphone many times, but George was always as

gentlemanly as ever, even if the news story was an unwelcome one. Stories come

and go, but George's class and kindness as a reporter will not be forgotten.

(Georgia Strait Bill Tielman

1999)

(4) It is rare in the media business, like any

other, to praise a competitor. But George Garrett is a rare competitor. In fact

Mr. Garrett belongs to all of us in a way few attain. He has had the grace to

help more than one new or late-arriving reporter to catch up on a story --

right after filing his own. His is a class act. His kindness and, yes,

old-fashioned gentlemanliness is as legendary as his industry and his

insatiable curiosity. He maintained both the trust of his contacts and

professional objectivity -- the recipe for routinely scooping all comers. When

he retires at the end of this month, CKNW will have lost a great

voice, and the rest of the media will praise him unstintingly. And they will

breathe a secret sigh of relief.

(Van Sun Editorial 1999)

(5) He's lucky he married the right woman.

When George Garrett was a little younger, Joan

Garrett usually answered the phone at 2 and 3 in the morning. It was his boss,

Warren Barker -- this, after her husband had already worked a day shift.

"He'd be so polite," said Garrett. “‘Oh,

hello, Joan, does George happen to be around?' Then I'd get to the phone and

he'd say, 'George, my boy, there seems to be a fire that sounds pretty good.

They found a body. Would you mind wandering by there?' "

Would Garrett mind? "No, I couldn't get out

fast enough." Twice, Joan saved him from driving through the garage door.

"That bloody door."

Nothing, not garage doors, not getting pounded in

the

CKNW's top dog has been driving his

competitors’ nuts by scooping everybody in town, day after day for 43 years.

But this is the end. George Garrett, 64, will sign off for the last time on

Friday, Jan. 29. He started on

Nice symmetry for a man who likes order in all

things. The man they call Gentleman George is as dapper as Fred Astaire, with buffed black-tasselled

slip-ons and a small black comb to smooth his perfectly side-parted grey hair.

He wipes his famously bucked front teeth with a pressed and folded white

handkerchief. Something to do with scum, he says, and "because my wife

tells me to." All this grooming, for a man his public never sees.

Garrett's perfectionism has made him far and away

the most respected working journalist in B.C. Garrett gets it right, and over

the years even the twitchiest sources have learned that he'll nail the details

and deliver the story straight and fair. As a result, nobody has sources like

Garrett. At the moment he has 1,118 names in his Casio electronic organizer.

Reporters joke that when he dies, they want to be named in the will for the

Casio.

His integrity and humanity are, if anything, more

legendary than his accuracy. He has always helped other reporters. He has held

stories rather than burn a source, harm a police

investigation or hurt someone unnecessarily.

He was the first to know of former

Sometimes he didn't have the nerve to ask the tough

questions. In 1978 he didn't have the guts to knock on B.C. Court of Appeal

Chief Justice John Farris's front door and ask him if he was cavorting with the

prostitute Wendy King. He got beaten on the story.

He's still visibly pained about some stories he was

forced to air. In 1978, Garrett was on a police ride-along, tape recorder

running, when the officers pulled over a stumbling-drunk B.C. Supreme Court

Justice E. Davie Fulton at 70th and Granville.

Garrett's invincibility on the crime-and-cops beat

comes from being around first and longest. He was the only night man when he

started as a reporter at 'NW. "That's how I got to know a lot of cops. I

showed up at every two-car accident, and I did a lot of running. When I moved

up to day shift I was still the only guy. I used to cover the court house, city

hall, and cop shop, anything that happened like a fire or a murder, news

conferences. I literally would run from the police station to my car, to city

hall, up the steps and away you go. I loved it."

He still runs all day. His alarm is set for

He doesn't regret not being around more for his

kids. "Joan has often said she'd never say 'It's me or your job' because

she knows she'd lose." She knew what she was getting when she married him

43 years ago. He's got no bad habits -- no boozing, no smoking, no womanizing

-- just an addiction to news.

In days past, he'd hang out at the police station

nights, weekends, after hours. One disgruntled member of the force gave him a

key to the fourth floor, which let him wander into the major- crimes unit. The

cops let him listen to wiretaps before they were authorized. "They used to

climb telephone poles and they'd say 'Hey, George, come and listen to this

tape.'"

He drank with them back in the '50s, too, when the

detectives got together and had a party at the end of a murder case, especially

if there was a conviction. "Some of them were in the back of the old city

morgue and I'd walk by old Doc Harmon doing his autopsy and join the guys having

a drink."

Garrett and those cops grew up together, which is

part of the reason he's ending his career on a journalistic high. He's doing a

series now on the disastrous morale in the police department, his daily stories

sourced by officers he's known for years. They're talking to him in their cars,

or insisting on using land phone lines rather then cell phones. "They know

if they get caught talking to me they're toast."

Garrett cares deeply about the health of the police

department, and he makes no bones about what he thinks

needs to be done. On Philip Till's show Thursday night, Till called him

"the man who wants to bring down the police department before he

retires." Garrett replied: "No, just the chief."

That's Chief Bruce Chambers, the only police chief

in four decades who won't talk to George Garrett.

Garrett is almost stumped when he's asked who he's

disliked over the years, but it's Chambers he finally

names. "That's not personal, it's what I feel he's done to the department

. . . They're behind the eight ball, they're 90 members short on training, and

it'll take a year or more to get them up to speed. They didn't anticipate the

retirements. A lot of people have taken early retirement because they can't

stand this guy.

"I talked to an inspector I know very well and

I said 'Am I on the right track?' He said, 'George, it's a mess, this guy is

not a leader,' meaning the chief. People may think its some kind of vendetta,

but in my mind it's not. It's a responsibility to the working members of the force,

to make sure their frustrations are known."

Garrett's ethics compel him to go after Chambers, and they're the only thing that ever stopped him

from getting a story to air. Injury and loss never have. He kept working in

1987 when his only son and youngest child, Ken, drowned in a canoeing accident

near

The most famous obstacle Garrett ever faced was

when he covered the

Garrett still didn't stop. He drove himself back

from hospital, through the ghetto, to his hotel, and proceeded to file a story

on carjackings, all the while spitting blood on to

his notebook. He came back to

It's a long way from

He has never asked for a raise, although he gets a Buick Regal compliments of the station.

He wanted to retire a year ago, but his bosses

wouldn't let him. So he struck a deal: two months on, two off. Then he made a

few mistakes on stories and couldn't shake the feeling that he was slipping.

Now he's going on to another career. As George Garrett Consulting, he'll tell

police how to deal with the media. People keep telling him to write his

memoirs, but he never kept a diary and says he's not sure he can remember what

he'd need.

He'll golf a little, maybe join a gym. He doesn't

really have hobbies. "My work is my hobby."

His idols? "Hmm.

Well, I deeply love my wife. I'd say she's an idol. My family, of course, and

we're very fortunate to have two great sons-in-law. Politically, I thought a

great deal of W.A.C. Bennett. He was a very nice man. I had respect for Bill

Bennett because I thought he was a great manager."

He chokes up when he talks about Warren Barker, 'NW

news director for 32 years. It was Barker who took him back after Garrett

detoured out of news between 1964 and 1976, and finally got fired as station

manager in Trail. "I came back with my tail between my legs and went to

see Warren, whom I idolized. He said, 'You have a job and I'll pay you the

highest that I can for a newsman.' It meant so much. Then after I'd been back

for a couple of years he made me a so- called investigative reporter, which

meant that I could just go dig. He never let me down."

Reporters he most admires? The three Jacks --

Webster, Wasserman and Brooks; Tom Ardies; and -- the

only one still working -- Tom Barrett of The Sun.

Garrett may be famous for modesty, but he wants a

mighty fine goodbye. He wants a reporters' party at a restaurant somewhere, and

he's thrilled that a massive roast is being organized to see him on his way.

After his last day at work, he'll go out for dinner with Joan, his daughters

Linda, and

Lorrie, and their husbands.

After Friday, there will be a huge hole in

He leaves us, at least, with hints of a tantalizing

Garrett tip, this one about the APEC debacle. "I don't think the RCMP did

everything right nor do I think they did everything wrong. I think there's a

valid reason for them acting very quickly to get people out of the way. I know

what it is, but I can't tell you. It's part of the evidence, and I haven't used

it because I think it would harm the commission." George

Garrett - to the end.

(Elizabeth Aird Vancouver

Sun 1999)

(6) Garrett has twice been severely injured on the

job, once while reporting from a war zone, once in a ferry lineup. While

covering the 1992 Los Angeles riots after the Rodney King trial, Garrett was

phoning in a report (``live'') when he was attacked on the street by four

thugs, one of whom crushed Garrett's jaw, nose and cheekbone with one punch and

stole his tape recorder. This summer, returning from a legislative session,

Garrett's car was broadsided by a cement truck on the Tsawwassen

causeway. He took 30 stitches to the head, suffered bruised ribs and bleeding

contusions in one lung. He believes the fact that he prefers heavy cars saved

his life.

Fractures, stitches and prolonged pain are a heavy

price to pay for the most prestigious journalism award in the province, but

Garrett figures he got a deal.

Returning a call from

If Garrett is a timely choice, I think it will also

be a popular one. It's hard to gauge the radio audience's opinion of Garrett,

but in the media community, he is regarded with great affection and deep

respect. He is scrupulously fair. His reports are balanced. He is compassionate

but does his work with objectivity. He is proud of his profession but has no

visible ego. For that alone, may God, Hutchison and Webster bless him. (Sun

Denny Boyd 1996)

Born

(Nov 16/34)