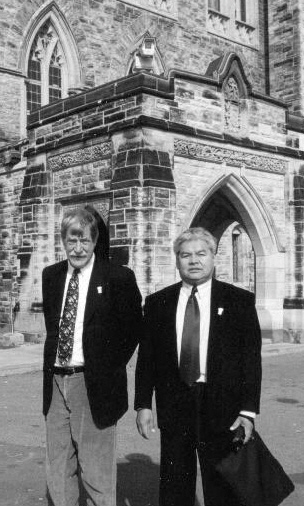

Bob Spence left

with Nisga

leader, Eric Grandison

Bob Spence - Host/interviewer Vancouver Show CKVU-TV Vancouver late 1970s-early

1980s; host Early Edition CBC Vancouver; talk show host CJOR Vancouver mid

1980s; facilitator Centre for Executive and Management Development Vancouver

late 1990s. Died

***

DIED: Robert (Bob) Spence, 53, a writer, broadcaster and

filmmaker; after a brief illness, in

***

"He was certainly

one of the brightest guys I ever worked with," Larry Langley said.

"Clever, thoughtful, he cared about people. Bob Spence was a remarkable

guy who lived life to the fullest."

***

1993

A colleague and I were more or less earnestly discussing the

state of the media around town last week, the problems at ACCESS TV, CBC, CFRN. The conversation eventually turned to the salad days

of

Wonder what ever happened to Bob Spence, who hosted the old Come

Alive program on ACCESS and

Could it be the maudlin whining of the chronologically

challenged? Things just seemed better on the local boxes then, livelier,

gutsier, more inspired. And Spence was a part of those

times in

Cosmic? Two days later my old crony Spence is

on the line, intoning in the familiar basso that he'd be in town Sunday for a

couple of days.

The occasion of the visit is a local workshop he's conducting to

an audience of certain federal government bureaucrats who do not wish to be

identified.

Spence, whose career profile in journalism seemed right out of

Central Casting, has ended up on what some (not him!) might consider to be the other side of the big fence.

These days, rather than saute cabinet

ministers, Indian chiefs or forestry execs, Spence teaches these same would-be

victims how to avoid the roaster.

Notwithstanding the track record, he says he'll "never be a

broadcaster again." Ever.

The road from cub to consultant is a long and winding affair,

not unlike the byways of the

Born in

Wee Robbie was a big reader, moving from Hemingway to Kerouac to

Farley Mowat to I.F. Stone. Picking up a poli-sci degree at the big school up the street, he managed

to taste something of

Along the way there have been stints as a DJ at a Granville

Island nightclub, tenure as the foreign affairs desk at the Georgia Strait,

covering the Portuguese revolution for the Sunday Times, work for the British

Consumers Association among other diversions. Covering two UN conferences in

In fairly short order, he nailed a job hosting ACCESS TV's

then-flagship morning show Come Alive in

"It was a fabulous experience. So many film-makers got

their start at ACCESS; practically the whole establishment in the West worked

there. We'd go to

"I've always had a special feeling for this place. It may

not be a popular view, but I still contend that there is a cultural maturity

and certainty in

"At CBC, working with people like Jay Mowat,

Roger Bill, Eric Moncur and Dolares

McFarland was great. I mean, management at that time just handed us a radio

program. We broke stories, we raised hell, informed people - and rose in the

ratings to second place. The same thing happened when I moved back to

Never short on opinions, Spence pronounces the current era as

dark times for electronic media, especially at CBC-TV.

"I've got so I just can't watch (CBC Prime Time News)

anymore. The whole `happification' of news, of target

marketing, the idea of `you tell us what you want and we'll deliver' is a

complete abdication of journalistic responsibility. Gutless,bonehead management has become the order of the day.

. . . We have an audience that has been de-sensitized with stuff like Cops and

Rescue 911. And we all know that the bottom line, that business dominates the

newsroom. We have no standards in

"When I was at CJOR (talk radio in

"CBC-TV should be completely destroyed and re-constructed

without hiring any (management) back. That might save it, because (the current

regime) has rendered it completely irrelevant at a time when we need it the

most."

One of the rare times the former employee has agreed with the

"I've got an extensive library of Canadian military history

and have followed it since I was a kid. And I'll you I support the ombudsman's

report. This was a sloppy job, bad history, a perversion of events. Our

veterans deserve better."

Much sunnier, apparently, is his own current work as a

small-scale, if generally satisfied consultant. The client list is diverse,

expanding, and somehow, Spence finds the notions of conflict resolution and

consensus building a tad more fulfilling than the ratings and rantings of TV/radio circa 1993.

"I'm really just helping people and organizations to tell their

own stories. I never counsel anyone to lie and I've turned down big money from

all three parties to become a spin doctor. The question is,

is public policy better served by people who are prepared or unprepared. It's

interesting work."

***

2001 -

Down the spindly,

car-choked streets around the

They weave their way beneath a canopy of trees and grind to a

stop. Firefighters, big guys in belts and boots, hop out and clomp down the

hospital-clean corridors of the palliative care unit to Room 351.

They are coming to see Bob Spence, a 53-year-old journalist,

advocate for the Nisga'a treaty, filmmaker, media

trainer and friend of firefighters. Such a friend that firefighters say he

probably got closer to them than any other civilian in the city's history.

He was their kid, really. It was the guys in No. 12 fire hall in

Kitsilano who helped raise him in the 1950s and

1960s.

That was back in the days when much of the world was grounded on

bedrock beliefs, like the one about a boy needing a dad.

Spence didn't have one. His father, a

When the boy grew up to be a man, he became a scholar at the

When word got out last spring that "Bobby" was

seriously ill with cancer, the pilgrimage from fire hall to bedside began. They

came, bearing firemen's hats, cards, pictures and stories of the way things

were.

They came on a Tuesday morning when Spence, with his wife Anne

close by, was visited by a reporter, his ubiquitous pack of Player's Light

cigarettes perched on his rickety knees.

Ah, the stories. Sometimes, he would tell them with the clarity

of the

Stories about how he used to close the big doors at No. 12 after

the crews left on a mission, how he would start a big urn of coffee for their

return. One firefighter instilled in him a life-long love of history; another

taught him how to box in the basement of the grand old building. With that

trademark laugh, a little gravelly now, he told how the men had to keep him

hidden from the chief the time he got a bloody nose in a basement boxing bout.

"I love them," he said between puffs. "I will

never be able to pay them back."

Retired firefighter Bill Hadley can still see Spence as a kid pedalling over to the fire station on his bike. Hadley was

at No. 12 during Spence's growing-up years. Then when Spence became a teenager,

he babysat Hadley's kids. They called him "Uncle Bobby."

Hadley said the special relationship firefighters developed with

Spence probably couldn't happen today. "Those were the days when kids used

to come over to look at the rigs holding their daddy's hand. The job has

changed so much. And it's more like a me, me, me

society."

As a kid, Spence did his part, too. He became a kind of mascot

around the fire hall and a gopher, fetching smokes and candy bars and even

groceries for the firefighters when they worked long Saturday shifts.

"They used to sic me on this firefighter who would talk too

much. Man, could he yak, normally about bullshit."

They used to check his report cards at the fire hall. Smart kid. Don't be a firefighter,

they told him. Be a lawyer so you can handle our divorces or a doctor so you

can handle our prostate problems, they would joke with him. Firefighters, he

says, are earthy, a little crude and very direct with each other. Then they'd

chase him to the boot locker to do his homework.

There was this time he badly injured his knee playing rugby and

football in high school. The firefighters ministered to him at the hall with

the softness of suburban dads.

Ah, the stories.

When he turned 16, they had a party at the hall, gave him a pen-

and-pencil set and a kick in the rear. "From now on, you will not take a

dime from your mother," they told him, and they helped him to find odd

jobs, including one driving an ambulance. Mostly, it seems, he transported dead

bodies.

Boys grow up. They leave their childish ways. But Spence never

forgot these guys. He had developed a special appreciation for this breed of

worker whose job takes them to the front lines of hell. Inside him was a fire

burning bright.

An intellectual with an anti-intellectual streak, he got a

master's degree, was part way through a doctorate degree when he abandoned it

and headed into life as a peripatetic contract worker in the media. Starting

with the Sunday Times of

When he returned to

Sitting in a wheelchair, greeting doctors and nurses as they

walked past, he cheerfully chirped, too, about his screw-ups, like the time he

froze-up for 90 seconds while hosting Cross Country Checkup ("That was my

last check-up."), about his battles with the broadcast brass and of his

aversion to all this "affirmative action, feminist stuff" that was

working its way into the CBC.

About 10 years ago, he left television and became a media

trainer through a company called Kicking Horse Productions. Finally, he wound

up being a point man for the Nisga'a in the days

leading up to the signing of their landmark treaty, travelling

up north and to Ottawa, helping the Indian band to craft their message and to

explain the finer details of the treaty to the media, lawyers and politicians.

Robb Lucy, now a communications strategist for young companies,

met Spence in the late 1970s when the two were working for the CBC in

"I still get comments from people up in Edmonton saying he

was the best host they had up there in Alberta," said Lucy. "He was

such a great perceptive Mr. Interrogator. He knew what to ask, when to ask it

and when to leave the pause. He has a great sense of humour."

As a journalist, Spence had this ability to bring complex things

together and a creative spark that, once lit, would keep burning for hours,

Lucy said. "He covered both sides of the pendulum from the soft spiritual

to hard journalism."

Larry Langley, an Edmonton city councillor

who co-hosted the CBC morning show with Spence for three years beginning in

late 1970s, said that of his 30 years in broadcast journalism, those three years

were the best.

He and Spence floundered at first. But he recalls coming in one

morning at

Spence, he said, was "the brains" while he was the

"announcer." Spence did all the economic and political interviews and

he was good at it. "When he got into something, he hung onto it like a

terrier."

They had decidedly different personal lives. "He used to

call me this prematurely greying father of

four." Spence, who was a bit of a roue,

"was a 30-year-old being a 22-year-old."

With a laugh,

Others saw more of his creative side. From his home in Kaslo in the

But White said Spence was always a writer first. "He's a

great talker, a great storyteller. He can wax eloquent on any subject and never

lose his way. He has been an inspiration for me in how you greet life."

With Spence, it was always with tremendous enthusiasm, he said.

White said Spence had the potential of having a great career in

journalism and political science but it was never fully realized because he

didn't like fame.

Spence himself said that he was never comfortable with his name

in the limelight and that he made a strategic mistake at one point in his

broadcast career by choosing

The erudite journalist never stopped speaking up for

firefighters. Having a scanner at home that picked up their calls, he would often

head out to fires. For him, they were social occasions, a chance to see his old

buddies and to set the odd cranky taxpayer straight:

How do you know there are too many fire trucks? How do they know

how many to send until they get here? They can always turn back if they aren't

needed. They need lots of cover for an alarm. They need your support.

"He is such a dear friend," said Captain Rob

Jones-Cook, who handles public relations for the department. He credits Spence

with teaching him how to do his job.

According to Lucy and White, Spence was always drawn to the

working man, having a strong interest in the Wobblies,

the torchbearers for the modern labour movement, in

the

In what he described as a watershed moment in his career, he

refused to cross an electricians' picket line at CBC because his father would

have been ashamed of him. "He would have rolled over in his grave."

As for the interest in soldiers and the military, he said many of the

firefighters at Station 12 were war vets who had been redeployed there.

These were the men who had helped to turn a boy into a man. A fire burning bright.