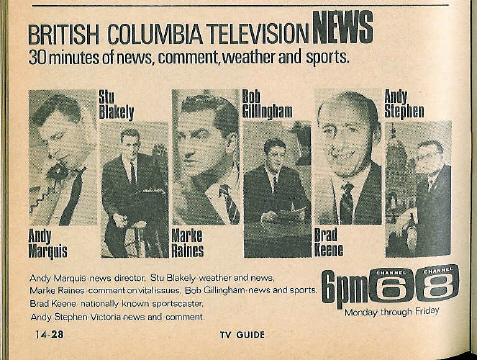

Andy Stephen

Stephen

had come out of Lorne Greene's broadcasting school in the post-war days, went

to CFRA Ottawa, and then came west in 1953 to be part of Dave Armstrong's CKDA.

When Armstrong set up CHEK TV, it was natural that Stephen would add "TV

news" to his duties.

"Andy

worked incredibly long hours," recalls Dave Roegele, who called Victoria

Maple Leafs hockey and pro wrestling on CHEK, and also co-hosted the mid-day

talk shows, first with Willie Taylor and then Ida Clarkson. "He'd be on

the air at 7 a.m. (on CKDA), and still be around for 6 to 7 p.m. on TV."

Times Colonist

July 11/04 drew snider excerpts

A profile of Andy Stephens

It was April 24, 1960. Const. Robert Kirby of the Saanich

Police Department was on patrol. One of his general orders was to be on the

lookout for a mental patient who had escaped earlier in the day. There was also

a break-and-enter that had to be investigated.

Then someone reported seeing the mental patient going into

what was then a wooded area near Viaduct Avenue and Markham Street. Kirby was

nearest.

Getting out of his car, Kirby had no way of knowing that the

mental patient had committed the B&E and that one of the things he had

taken was a loaded rifle.

Moments later, Kirby -- immensely popular and father of two

small children -- was dead.

Three thousand people came to the funeral. It was one of the

first of what became a poignant Canadian tradition, in which every department

in the country sends a representative to the funeral of a comrade killed in the

line of duty.

It was also one of the first "hard" news stories

covered on television in Victoria.

It had been less than seven years since TV had arrived in

southern British Columbia, and less than three since Dave Armstrong, owner of

CKDA Radio, launched CHEK TV. For a lot of people in Victoria, TV was still

establishing itself as a medium to be taken seriously. In the days following

April 24, 1960, it became apparent they were not welcome at a sorrowful

occasion.

"We caught (a lot of heat) from the public for

that," recalls CHEK's pioneer news anchor, Andy Stephen. "We shot (the

aftermath of) the incident from a distance, and covered the funeral procession

-- we weren't allowed into the church -- and people didn't think we should be

there (covering the procession)."

But whether they liked it or not, Victorians were getting a

glimpse of the niche television was carving for itself as an information

medium.

News and information are the staple of any television

station. TV newscasts of 50 years ago are quaint to look at today. The earliest

newscasts at CBUT Vancouver were introduced by a simple "art card"

proclaiming "CBC TELEVISION NEWS," accompanied by a few bars of

frenetic, dramatic, symphonic music, then the picture would dissolve to (in the

present case in one's mind's eye) Gordon Inglis, dark wavy hair and pencil

moustache, sitting at a desk.

"Talking heads" have long been anathema to

television, but in the early days of TV, the fact that you could see anything

on that box - - including a man in a suit reading a script -- was fascinating

enough.

When there were film clips, they were silent, covered with

more music, and timeliness didn't always matter. In 1955, CBUT Vancouver

reported on the death of Albert Einstein with Inglis announcing that

"earlier this week, we told you about the passing of Albert Einstein."

In other words, they'd already reported on Einstein's death, but now they had

film. The film showed Princeton University, Einstein shaking somebody's hand,

and then Einstein looking whimsically at the camera over his glasses. This was

repeated twice (three "loops" in all), while Inglis read the

obituary.

The shock of the killing of Const. Kirby was multiplied by

the fact that very little "hard" news actually happened in Victoria.

The capital had a well-deserved reputation as a quiet place where nothing

happened. As recently as the early 1980s, a gas station robbery would be a

"lead."

"It was a clean-living town," Stephen says.

"If you got a car stolen, it was a big deal."

Stephen had come out of Lorne Greene's broadcasting school in

the post-war days, went to CFRA Ottawa, and then came west in 1953 to be part

of Dave Armstrong's CKDA. When Armstrong set up CHEK TV, it was natural that

Stephen would add "TV news" to his duties.

"Andy worked incredibly long hours," recalls Dave

Roegele, who called Victoria Maple Leafs hockey and pro wrestling on CHEK, and

also co-hosted the mid-day talk shows, first with Willie Taylor and then Ida

Clarkson. "He'd be on the air at 7 a.m. (on CKDA), and still be around for

6 to 7 p.m. on TV."

"I'd do the morning news at CKDA," says Stephen,

"and around 9 or 10, my two cameramen, Joergen Svendsen and Karl Spreitz,

would come in to get their assignments. They'd go out, shoot the film, then

have it back to the station by 3:30 for editing and presentation at 5:30."

There was no time to be artistic: get the pictures, get them

back to the lab, get them on the air. The Kirby funeral was a case in point:

while mourners were paying their respects and comforting the grieving family,

the cameramen were doing their job with dispassionate professionalism -- it

could have been the accustomed assignment fare of a house fire, an interview or

the latest Super- Valu opening. That's probably why people at the funeral

resented them.

Back at the studio, Svendsen and Spreitz would rush their

films through the lab, then hang them on wire racks over an electric hotplate

to dry.

Interviews involved an additional step: synchronizing the

audio tape with the film. That was eventually eliminated when the Auricon

camera came along, with a magnetic strip built onto the film.

"Once the film was dry," says Stephen, "we'd

edit it and I'd write the script to go with it."

Stephen definitely was the CHEK TV news department.

Victoria news tended to fall into two principal categories: provincial

politics and personalities. As one of the first "electronic"

journalists to work at the "Rock Palace," Stephen found a prejudice

in the press gallery against anyone with a camera or a microphone.

"The print guys thought it was their right to report on

the 'ledge,' " says Stephen.

It's hard to say why. Perhaps microphones and cameras seemed

like smuggling a pocket calculator into a math exam.

But Stephen persisted, and with the help of some early allies

like Ian Street of the Daily Colonist and Alec Young of the Vancouver Sun,

radio and TV gained acceptance.

"I'd invite them (his detractors) on Capital Comment,

" he says, referring to the public-affairs roundtable he hosted for more

than 20 years. "They'd be seen all over the south Island and Lower

Mainland, and then when CHAN picked it up, they'd be seen all over the

province." Soon, the critics began to see some value in the television

medium.

Stephen also struck up a friendship with W.A.C. Bennett. When

"Cec" was premier, Stephen says reporters like him, Nesbitt and

others could always knock on the premier's door or visit him at home.

"(Bennett) always had enough faith that we wouldn't

report something that we shouldn't."

As for "personality" news, even though celebrities

enjoyed the beauty and relative seclusion of Victoria, they were still willing

to grant interviews to local TV. Stephen's favourite interview guests included

Sebastian Cabot, Elsa Lanchester, Gordie Howe and Burt Reynolds. When Cabot

moved to Deep Cove, Stephen was a frequent visitor, and a walk down the street

would lead to a friendly feud over whose adoring public was calling to whom.

"Someone would yell, and I'd say, 'that was for me,' and

Cabot would say, 'No, that was for me. You can have the next one.' "

The fact that there was any argument at all shows how quickly

That Guy On The News had become a "personality," just like a popular

TV actor.

Half a century is an eye-blink if you're a biblical scholar.

With technology it's a different planet. In that time, TV news has gone from

silent film on a bed of elevator music to the maxim, "life has a

soundtrack -- let's hear it"; from a simple art card to that slick opening

title sequence; from Bob Fortune's weather blackboard and oversized chalk to

high-tech computer graphics; and that "in-depth team coverage" was

once a pair of film cameramen and an overworked newscaster.